Rechargeable batteries, what a marvelous convenience! More earth friendly, less waste, powering so many things in our modern world— what’s not to like? As it so happens, quite a lot. The commercials for our bright and shiny baubles don’t talk about the Congo.

Outsiders have long coveted the wealth of natural resources found in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Foreign entities preying on this “resource curse” have destabilized the country for hundreds of years. An ongoing state of civil war serves keep the country weak in the face of external threats, and it becomes self-sustaining as opposing factions profit from natural resource extraction. The grim results of this never-ending cycle: 4.5 million internally displaced Congolese need humanitarian assistance, and hundreds of thousands more have fled to neighboring countries. More than two million Congolese children are at risk of starvation.

Cobalt

Over 50% of the world’s cobalt comes from the DRC. Lithium-ion battery cathodes as well as numerous other industrial applications require cobalt. When the DRC recently announced increased taxes on mining (including a premium on cobalt) international mining conglomerates went ballistic and declared increased taxation ‘victimized’ cobalt consumers.

The true victims of cobalt mining are Congolese citizens, many of them children, who mine the mineral by hand with no protective equipment. Breathing problems and birth defects are common. Many reports of child labor, slavery, and hazardous working conditions make the situation especially dire. In this country where more than 77% of people live on less than $1.90 per day, cobalt miners are forced to tolerate terrible conditions.

Conflict Minerals

Cobalt demand is going up, adding incentive for various factions to raise revenue from cobalt mining. Human rights organizations like Amnesty International argue that cobalt should be added to the list of “Conflict Minerals.

“Currently regulated conflict minerals are referred to as “3TG,” which are columbite-tantalite, also known as coltan (from which tantalum is derived); cassiterite (tin); gold; wolframite (tungsten); or their derivatives; or any other mineral or its derivatives determined by the U.S. Secretary of State to be financing conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo or an adjoining country.”

Despite some industry push back, “there are few places in Congo today that are rebellion-free.” Specific companies, like Apple, finally recognized reality and agreed to voluntarily treat cobalt as a conflict mineral.

The U.S. Dodd-Frank Act Section 1502 and the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Conflict Minerals Rule had some effectiveness removing DRC conflict minerals from international supply chains. Unfortunately the long-term viability of section 1502 is not assured in the present U.S. political climate.

Evolution Of A Paradox

“Congo has become a never-ending nightmare, one of the bloodiest conflicts since World War II, with more than five million dead. It seems incomprehensible that the biggest country in sub-Saharan Africa and on paper one of the richest, teeming with copper, diamonds and gold, vast farmlands of spectacular fertility and enough hydropower to light up the continent, is now one of the poorest, most hopeless nations on earth.”

How did the Democratic Republic of Congo reach this point in its history? Colonialism wreaked havoc as Europeans and later Americans took shameless advantage of the land and its people. Add corruption in government and domestic instability and the picture becomes increasingly clear.

The first Europeans to venture to the Congo were Portuguese explorers who reached the mouth of the Congo River in the 15th century. They laid claim to the lower Congo River basin (120 navigable miles inland from the river’s mouth), but gorges and waterfalls prevented further exploration. This remained the full extent of European presence in the Congo for several hundred years. The Portuguese traded European goods with the Kingdom of Kongo for gold, copper, and other resources— including slaves. Portuguese slave traders took an estimated 350,000 people from the kingdom.

In the 19th century, the advances of the Industrial Revolution greatly increased Europe’s demand for raw materials. The easy availability of commodities like rubber, palm oil, and cotton drove the “scramble for Africa.” French naval officer Savorgnan de Brazza made it beyond the Portuguese and reached the upper Congo. He signed a treaty with the Batéké people and established a port at Ntambo. From that point the Congo River was navigable for over 1,000 miles, making much of central Africa accessible to the Europeans. King Leopold of Belgium hired Welsh explorer Henry M. Stanley to lead an expedition from the Atlantic Coast to Ntambo. Great Britain allied with Portugal and entered a treaty that purported to grant the British exclusive rights to navigate the Congo River.

Competing claims gave rise to the Berlin West Africa Conference. At the conference, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Great Britain, Portugal, Spain, the U.S., Austria, Russia, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Turkey planned to divide up trade in the Congo River basin. The U.S. favored Belgian claims ahead of time by recognizing the flag of King Leopold’s Association Internationale du Congo (AIC) on April 22, 1884. In the end, King Leopold’s “International Association of the Congo” became the de facto government of the Congo basin, and the territory was renamed “The Congo Free State.”

Belgian Terror

Despite agreements emanating from the Berlin West Africa Conference for civility and good governance of the Congo, Leopold converted the territory for use as his personal vassal state. Mark Twain’s 1905 satire, “King Leopold’s Soliloquy” captured the results of this travesty:

“They have told how for twenty years I have ruled the Congo State not as a trustee of the Powers, an agent, a subordinate, a foreman, but as a sovereign— sovereign over a fruitful domain four times as large as the German Empire — sovereign absolute, irresponsible, above all law; trampling the Berlin-made Congo charter under foot; barring out all foreign traders but myself; restricting commerce to myself, through concessionaires who are my creatures and confederates; seizing and holding the State as my personal property, the whole of its vast revenues as my private swag— mine, solely mine— claiming and holding its millions of people as my private property, my serfs, my slaves; their labor mine, with or without wage; the food they raise not their property but mine; the rubber, the ivory and all the other riches of the land mine— mine solely— and gathered for me by the men, the women and the little children under compulsion of lash and bullet, fire, starvation, mutilation and the halter.”

Leopold’s use of the territory as his private cash cow ended in 1908 when Belgium formally annexed the Congo, but natural resource extraction continued unabated. Europeans always profited handsomely at the Congo’s expense. The brutality of the colonizers toward indigenous Congolese took many forms: labor coercion, suppression of local political, social, and cultural traditions, forced migration, beatings, and mutilations. Resistance to colonial rule increased steadily.

Patrice Lumumba and Independence

The Congo remained in Belgian hands until independence in 1960, when Patrice Lumumba of the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) Party became the new country’s first Prime Minister. Lumumba believed that the Congo should be fully independent and its natural resources used for the benefit of the people. He spoke truth to power from the very beginning of his tenure (excerpt from Lumumba’s Independence Day Speech, June 30, 1960):

“This was our fate for 80 years of a colonial regime; our wounds are too fresh and too painful still for us to drive them from our memory. We have known harassing work, exacted in exchange for salaries which did not permit us to eat enough to drive away hunger, or to clothe ourselves, or to house ourselves decently, or to raise our children as creatures dear to us.

We have known ironies, insults, blows that we endured morning, noon and evening, because we are Negroes. Who will forget that to a Black one said “tu”, certainly not as to a friend, but because the more honorable “vous” was reserved for whites alone?

We have seen our lands seized in the name of allegedly legal laws, which in fact recognized only that might is right. We have seen that the law was not the same for a white and for a Black — accommodating for the first, cruel and inhuman for the other.

We have witnessed atrocious sufferings of those condemned for their political opinions or religious beliefs, exiled in their own country, their fate truly worse than death itself.

We have seen that in the towns there were magnificent houses for the whites and crumbling shanties for the Blacks; that a Black was not admitted in the motion-picture houses, in the restaurants, in the stores of the Europeans; that a Black traveled in the holds, at the feet of the whites in their luxury cabins.

Who will ever forget the massacres where so many of our brothers perished, the cells into which those who refused to submit to a regime of oppression and exploitation were thrown?”

Contemporaneous news reports revealed that Belgium and other Western countries did not respond well. Their “White Man’s Burden” perspective ignored the fledgling nation’s right of self-determination. The Eisenhower administration in particular saw Lumumba as a threat.

The Congo also experienced domestic unrest following independence. Resource-rich Katanga province rebels, prodded by Belgian mining companies that feared nationalization of the mines, pushed secession. The army revolted over both a pay dispute and the fact that all officers were Belgian. When Lumumba sought help from the West he got the cold shoulder.

The Soviet Union was more receptive, but Lumumba’s interaction with the U.S.S.R. put a veritable target on his back. The rabidly anti-Communist Dulles brothers thought Lumumba was destined to become “a Castro or worse.” Regime change machinations, culminating in a military coup led by newly promoted Army Chief of Staff Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, were initiated by U.S., U.K., and Belgium.

With the help of Mobutu, the conspiring nations delivered Lumumba into the hands of his bitter rival Moises Tshombe, secessionist leader of Katanga province. Lumumba and two of his allies were executed by firing squad in a Katanga forest and buried in a shallow grave. Several days later on macabre orders ostensibly from Belgium, soldiers exhumed the bodies of Lumumba and at least one of his comrades, subsequently dismembered them, and dissolved the remains in acid. The young man who had the temerity to stand up before the Belgian King and tell the truth about the Congolese people’s suffering threatened the status quo— even in death. Click To Tweet

Mobutu Sese Seko

After Lumumba’s death, the newly formed country began to fragment under the competing challenges of state secessionists, international corporate interference, and Cold War tension. Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, now known as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga (“The warrior who leaves a trail of fire in his path”) responded by converting the DRC from democracy to dictatorship with the help of the CIA. He renamed the country Zaïre, and became the “archetypal African dictator” from 1965 to 1997.

Over his 31 years in power, Mobutu Sese Seko looted over $5 billion from the DRC. He committed numerous crimes against humanity. Mobutu tried to create a positive legacy by offering to host refugees from the 1994 Rwandan genocide, but his lack of ability to manage the sheer numbers of people pouring across the border meant both victims and perpetrators entered the DRC. Rwandan ‘genocidaires’ established a government in exile in Goma, and atrocities continued.

Laurent Kabila

Beginning in 1963, Laurent Kabila and other former Lumumba supporters formed the People’s Revolutionary Party to foment rebellion against Mobutu. He spent 20 years living in exile in Tanzania. Finally in October 1996, with the backing of Rwanda and Uganda, Kabila led the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFL) against Mobutu’s forces in the First Congo War. The ADFL overpowered regime forces and Mobutu fled into exile on May 16, 1997. Kabila declared himself President the next day.

Initially the people were simply relieved to be rid of Mobutu. Over time, however, it became apparent that Kabila differed little from his predecessor. His regime was marked by authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights abuses. Kabila broke ties with his former patrons Rwanda and Uganda. In retaliation, the two nations invaded the DRC and began the Second Congo War. On January 16, 2001, Kabila was executed by one of his own kadogos (child soldiers).

Joseph Kabila

The younger Kabila came to power after his father’s assassination. Without his own mandate and base of support, Joseph Kabila simply retained his father’s retinue of strongmen and affiliates.

Now in power for 17 years, Kabila has quite simply overstayed his welcome. He refused to hold elections in 2016. A survey from January of this year showed only 7.8% of Congolese would vote for Kabila if he stood for reelection. Nonviolent protestors organized by the Catholic Church have been met by tear gas and live ammunition from Kabila’s state security services.

The upcoming December election may well see the DRC transition to a new head of state. Kabila’s regional allies have been ousted: Zuma in South Africa, dos Santos in Angola, and Mugabe in Zimbabwe.

Will The Destructive Cycle Remain Unbroken?

Although some positive developments would be most welcome, just today the United Nations Security Council expressed great concern over the deteriorating humanitarian situation in the DRC. Kabila has promised to step down and hold elections in December, but whether or not this actually happens remains to be seen.

Ultimately the people of the Democratic Republic of Congo will continue to suffer at the hands of corrupt dictators and avaricious corporations until fair elections are held, the UN is adequately funded and steps up engagement with peacekeepers, the DRC’s neighbors stop enabling Kabila, and corporations take active steps to clear their supply chains of conflict minerals.

I hope there’s another Patrice Lumumba out there.

The Ghion Journal is a reader and viewer funded endeavor. We disavow corporate contributions and depend only on the support of our audience to sustain us. The tip jar is earmarked to go directly to the writer, the link below is customized to directly to the author’s account. We thank you in advance for your kindness.

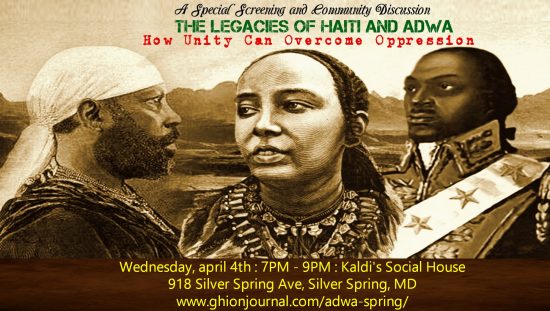

DMV Event: How Overcome Can Overcome Oppression

If we are to bend the arc of history towards justice, we can only do so through inclusiveness and by speaking truth to power without political, identity or ideological blinders. That is the aim of the event I’ll be hosting next Wednesday, April 4th, at Kaldi’s Social house. The event was inspired by one of the most widely read articles here at the Ghion Journal titled “Greater than Wakanda”. Click HERE or on the picture below to RSVP.

Holly Blomberg

Latest posts by Holly Blomberg (see all)

- Alex Jones: Our Canary In A Coal Mine - August 9, 2018

- Radical Malfeasance: Drugging Immigrant Kids And Dividing Families - June 23, 2018

- Those Crazy Baldheads: Toadies Of U.S. Imperialism - June 4, 2018